skip to main |

skip to sidebar

From the

Concord Monitor in New Hampshire:

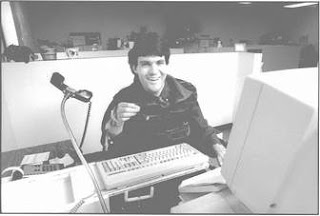

David Robar (pictured) was 26, an elite ski jumper from New London who tried out for the 1988 Olympic team, when a motorcycle accident left him paralyzed below the chest. He spent half a year in the hospital before emerging with a new passion in life.

Robar became an advocate in Concord and Washington, D.C., for people with disabilities, winning over lawmakers as he explained how various bills would give people like him the rights assumed by other Americans. Among his proudest accomplishments was the passage of a law that allowed people with disabilities to work without losing Medicaid benefits, a need Robar explained so convincingly that then-President Bill Clinton cited his story in speeches on the subject.

Robar died Sunday in his New London home of pneumonia related to his injury. He was 44. Those who knew him said his advocacy advanced the cause of thousands of people, while his personal warmth persuaded many newly disabled that they could lead full, though different, lives.

"He was tenacious when it came to the idea that people with disabilities should be considered equal citizens and have opportunities to achieve the American dream," said Clyde Terry, CEO of Granite State Independent Living, where Robar worked since 1992. "He wholeheartedly embraced his lot in life after his accident, and it didn't get him down, but rather he drew strength from that to say, 'I'm still a full human being and I can still make a difference.' "

Born in July 1964 in South Weymouth, Mass., Robar moved to New London with his family three years later. He and his sister and brother grew up skiing at King Ridge each Friday with their classmates, and Robar took to the slopes especially well.

He graduated from Kearsarge Regional High School in 1982 and went on to study civil technology at the Thompson School at the University of New Hampshire. He worked for builders in Nashua and Boston, but as the 1988 Winter Olympics drew near, he headed to Lake Placid, N.Y., and spent a year training for the trials. Though he did not make the team, competing in the trials was an achievement important to him throughout his life, said Jeff Dickinson, a friend and colleague who came to know Robar years after his accident.

"Once in a while when you got him to talk about it, it was really an important thing for him that he had excelled to that extent," Dickinson said. "For a lot of folks it would be really hard to go from that to having a disability where you weren't able to be as athletic. . . . He just sort of shifted his focus, and he brought as much passion for advocacy and politics later in life as he had younger in life as an athlete."

Robar had returned home to study at New England College when a motorcycle accident in October 1990 injured his spinal cord. He was left paralyzed from the top of his chest down and could not move his hands. He needed a high-tech wheelchair to move, and attendants to help him get out of bed each morning. Despite this, his mother said, he did not succumb to depression.

"When he was first injured, he said, 'My life will be different, but my life will be good,' " Elaine Robar said. "And he just kept going that way, he really did."

Robar took great pride in living independently, she said, and did not move back home after the accident. He rented an apartment and then bought a house across the street from his parents in New London. He loved driving his van, navigating by voice to his many meetings.

He worked a number of jobs during his 17 years at Granite State Independent Living, editing the nonprofit's newsletter and coordinating events before turning to advocacy. While working on a contest for adaptive technologies, his parents said, he met Dean Kamen and became an early tester for the inventor's iBOT wheelchair, a predecessor to the Segway scooter. The iBOT functions like a standard power wheelchair but also allows users to raise themselves to reach high shelves, climb up and down staircases and cross uneven terrain.

"It was a big secret," said his father, Donald Robar. "It was going to change the world for people with disabilities."

Robar did not end up using the iBOT, but he would use his power wheelchair to whiz around the office of Granite State Independent Living, said Norma Lemire, his supervisor in recent years.

He never regained use of his fingers, and so colleagues saw him typing grants with the use of a strap-on device. Though upbeat, he confided from time to time with other wheelchair users about the chronic pain and pressure wounds that had become part of their lives, said Mark Race, a friend and colleague who also has a spinal cord injury.

From a young man who knew little about politics, Donald Robar said, his son grew increasingly engaged as he saw firsthand how policy and lawmaking affect people with disabilities. He traveled often to Washington, D.C., and became a presence at the State House, as he testified and lobbied for various bills.

Robar was a skilled advocate who could persuade skeptics with such finesse that they sometimes took credit for his ideas, Race said.

"That way it would be win-win," he said. "He'd get you to think it was your idea."

His proudest accomplishment was working to pass a law that allows adults with disabilities to work full time while retaining their Medicaid benefits. Medicaid pays for certain needs, like personal aides, that some people with disabilities need so they can work, but full-time employment had disqualified some from the program. He spoke with Clinton about the issue at a roundtable during the president's second term, and his story became one Clinton told during speeches in favor of changing the law.

Robar spoke about his desire to work at the 2000 Democratic National Convention and kept photos of that appearance in his cubicle for years after, a colleague said. He was also present when then-Gov. Jeanne Shaheen signed the change into New Hampshire law in 2001.

The charisma that contributed to his political success made him comfortable with the national media, persuasive among legislators and inspiring to individuals recently affected by spinal cord injuries, Lemire said.

"People would gravitate toward him," she said. "There was just something about him that was truly, truly more than charming. It was magnetic."

Robar spoke out during the 2008 campaign in favor of stem cell research. As his health declined in recent months, he remained focused on expanding rights for the disabled and longed to return to work, Lemire said.

"I think his disability probably in some strange way challenged him, and he responded so that it brought out the very best he had to offer this life," she said.

From the Concord Monitor in New Hampshire:

From the Concord Monitor in New Hampshire: