From The Acorn at Drew University:

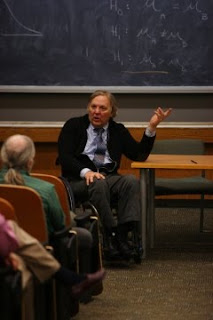

From The Acorn at Drew University:Renowned journalist and paraplegic John Hockenberry (pictured) visited Drew University on April 14 as a guest speaker. Hockenberry was introduced as both a journalist and as the host for National Public Radio’s The Takeaway. He has also won four Emmy Awards and three Peabody Awards. “It’s great to see a university of such a small size constituting a sense of community,” Hockenberry said at the beginning of the lecture.

Hockenberry started by explaining that he never expected to be a person with a disability. Once he became one, he didn’t expect to be able to accomplish or pursue the things he could as a person without a disability. “Our society focuses on normalcy,” Hockenberry said. “Being disabled is a remote experience.” He polled the room on how many people knew someone with a disability and how many had one themselves.Using the results of this poll, he pointed out that we live in a society that is actually abundant with disabled persons. Despite the fact that many of us seem to know a disabled person, it’s still difficult to relate to disability. “Our society values ‘normal,’” Hockenberry said. “But if you’re normal you also have to be in the Olympics.” He explained that, as a society, we love and hate normalcy. Sometimes we yearn for normalcy but feel abnormal, or vice versa.

When his first set of twins was born, Hockenberry expressed his fascination with how the majority of his household could now not walk. “I had been in a wheelchair for about 20 years when Zoe and Olivia were born,” he said. “I went from being the one person in the house who couldn’t walk to being one of three who couldn’t walk [as the other two were newborns]. I almost missed the sense of solidarity.” With a laugh, he told the audience how he was used to feeling like the only disabled person in the whole entire world and how he now felt like the only disabled person in the whole entire world with twins. “I realized that, in fact, my wife was going through it too. It was me and my wife who had just had twins, and my disability was just a part of the whole thing—not the main aspect,” he said.

Hockenberry went on to describe how each of his daughters approached learning to move extremely differently. Zoe got on her stomach and put her arms in the air. “She’d lift her arms and legs in the air at once, like a sea turtle. It was ridiculous,” Hockenberry said. Olivia loved the wheelchair and used it to stand up. Over time, she got better and better at it. He and his wife both thought that Olivia would be the first to move on her own, until one day Hockenberry sat on the couch putting on his shoes. “I picked up Zoe and put her in the wheelchair,” said Hockenberry. “Olivia was doing her thing, holding onto the chair. Zoe sat in the chair … and used her arms to roll the wheels and push the chair across the room.” Hockenberry realized that they’d each decided—in their own way—how to move around. Although he and his wife had originally thought there was something wrong with them because of their abnormal ways of getting around, Hockenberry came to the conclusion that “normalcy” is a concept crafted by parents.

“When I first got my spinal cord injury, I wheeled out of the hospital with a bright orange chair,” Hockenberry said. “It was sort of a way to say, ‘Hah! I’m proud of my chair!’” He described how, no matter what he did, people noticed him right away. People’s reactions were all different—from pulling their kids closer to themselves as he passed to asking him if he needed help wheeling up a hill. “When I realized I was going to be a paraplegic, I remembered experiences with disabled people that I’d had earlier in my life,” he said. “My mother always told me not to stare, and that always made me think that there was something wrong, a reason I couldn’t look.” Hockenberry spoke of how much anxiety he felt when he was first confined to his wheelchair. He couldn’t understand why people stared and what he was doing wrong. “It caused me a lot of anxiety that didn’t change until my six-year-olds were looking at my wheelchair catalogue,” Hockenberry said.

His daughters told him to get a wheelchair with sparkly wheels. When he laughed and told them he couldn’t, Hockenberry explained that his daughters’ expressions were unforgettable. “It was as if they were thinking, ‘wow, you’re a paraplegic, and you can’t have sparkly wheels?’” he said. “I started to think of the chair not as something you sat in because you were sick, but something you’d use to enhance your mobility. They have chairs for tennis, for basketball, for driving.” Hockenberry then wheeled over to the light switch and shut off the lights. He moved to the front of the room, showing the audience his sparkly wheels. “It’s like a magic carpet and has nothing to do with a disability anymore,” he said.

Hockenberry said that the sparkly wheels changed everything—everyone’s attitudes changed when they saw his chair. “I wasn’t in the chair,” he said, “The chair wasn’t helping some infirmity. I didn’t question myself anymore.” Because everyone’s reactions changed, his and their preconceived notions changed with just one gesture.Hockenberry also focused on wartime. In a time of war, societies tend to become more comfortable with people with disabilities. He told the audience of his grandfather’s loss of an arm and how he adapted to the world around him. “He used his stump to tie his shoes—even throw a baseball,” Hockenberry said. “My brother used to get paid a quarter from his friends for a chance to see my grandfather’s stump in action.”

Hockenberry showed the audience that being disabled isn’t something that should take over someone’s life. He explained that normalcy is something we all strive for, as well as something we all fear. On a closing note, Hockenberry wheeled to the center of the room with a smile and said, “May we all have sparkly wheels.”