From Brian Stelter at

The NY Times. (Thanks Brian for the excellent story!)

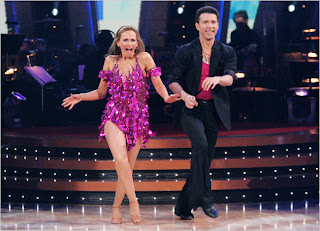

The actress Marlee Matlin (pictured) shimmied her way onto “Dancing With the Stars” two years ago, memorably using sign language to tell viewers to “read my hips.” But when Ms. Matlin, who is deaf, went to ABC.com to watch a replay of the show, she was impeded because the network’s videos were missing captions.

Closed-captioning is mandatory on television, but not for TV programs on the Internet. And that has turned Web sites like ABC.com into battlegrounds for advocates like Ms. Matlin, who have spoken up on the lack of captions on sites like CNN.com and services like Netflix.

Media companies say they are working hard to make online video more accessible. YouTube, the world’s biggest video Web site by far, now supplies mostly accurate captions using voice-recognition software. ESPN is offering captions for its live streams of World Cup matches. And ABC now applies the TV captions for “Dancing With the Stars” to ABC.com.

But big gaps remain much to the dismay of deaf Web users. Television episodes on CBS.com, news videos on CNN.com and entertainment clips on MSN.com all lack captions, to name a few.

Other Web sites, like NBC.com, are inconsistent about captioning, so “America’s Got Talent” has captions but “The Marriage Ref” does not.

As online video becomes ever more popular, deaf viewers face the prospect of a partly inaccessible Internet.

“We do not want to be left behind as television moves to the Internet,” said Rosaline Crawford, the director of the law and advocacy center for the National Association of the Deaf.

The Hearing Loss Association of America says that 36 million Americans have some degree of hearing loss. Other groups, like English-language learners, also benefit from captions.

Groups like Ms. Crawford’s say they are merely fighting to maintain the access to television that they won a generation ago, in 1990, when Congress mandated closed captioning technology in virtually all TV sets, and in 1996, when Congress required most shows to have captions. “Every generation of technology that comes out seems to be a bit late on accessibility,” said Larry Goldberg, director of media access for WGBH, the PBS member station in Boston.

Advocates are pushing Congress to pass an update to the bill that would mandate captions on any online video that has also appeared on TV, like prime-time comedies and dramas, and would take other steps to make consumer electronics more accessible, by requiring closed-caption buttons on remote controls, for instance.

A Senate subcommittee held a hearing on the bill last month.

In written testimony, Ms. Matlin imagined trying to watch Neil Armstrong’s walk on the moon on the Web, but finding that his “giant leap for mankind” words had been “erased.” “That’s how taking closed captions out of broadcast content now being shown on the Internet feels to millions of people like myself,” she said.

The prospect of legislation is motivating some major Web site operators to add captions more quickly.

A collection of industry groups is close to finishing a universal standard for online captions, which would make it easier to adapt TV captions to other formats. “I think there’s a bit of foot-dragging based on waiting for that standard to be finished,” Mr. Goldberg said.

Advocates have been exceptionally vocal about the problem. Take Hulu, the biggest Web site for TV episode viewing, which offers captions in multiple languages for some shows (including many of its most popular ones), but not all.

It is pressing its content suppliers — networks and studios — for more captions. “Users send us feedback about closed captions more often than almost any other feature, so what started as a small side project has turned into a very important part of our user experience,” Eric Feng, the chief technical officer for Hulu, said in an e-mail message.

It is also a priority at YouTube, a unit of Google, where captions can be viewed for any video uploaded since April, as long as it is in English and has a clear audio track. The voice-recognition technology makes mistakes, but it has been lauded as a major improvement for deaf and hard of hearing Web users.

There is also a business reason for Google to be captioning, Mr. Goldberg said: “When you start adding text to all of your videos, search is aided tremendously.” Industry groups say captioning can be expensive in some cases, and they argue that poorly conceived rules could stifle innovation. But they acknowledge the value of captions.

Ken Harrenstien, a software engineer at YouTube and Google, who is deaf and who is heading the captions project, said the auto-captioning can be translated into more than 50 languages. But so far the technology recognizes only English-language audio, something that he said “we need to broaden.”

On other Web sites, captions are being added gradually — far more slowly than advocates would like.

Netflix came under fire last year for not having captions on its TV and movie streams. It said that reformatting its files to include the text would take software advancements and a huge amount of time. In April it announced that four seasons of “Lost” had been captioned, and that it would “be working to fill in the library over time.”

Among the big TV networks that stream full episodes online, most are captioned, with the biggest exception being CBS, which says it is now developing a video player program that will support captions. Anthony Soohoo, the senior vice president of CBS Interactive’s entertainment unit, said the site planned to release it in the fourth quarter.

Adding captions to the countless video clips on the Web is an even bigger hurdle, one that the bill largely leaves untouched. Software like YouTube’s, though, may help. Said Mr. Harrenstien, “Only a tiny percentage of the world’s videos are captioned, so we have a lot of work to do.”

From Brian Stelter at The NY Times. (Thanks Brian for the excellent story!)

From Brian Stelter at The NY Times. (Thanks Brian for the excellent story!)